The Life Cycle of a Frog

Frogs are one of the most varied species on the planet. They come in different sizes, shapes, and colors; they can radically differ in habitat, lifespan, and social behaviors; and they even engage in various courtship, mating, and egg-laying behaviors.

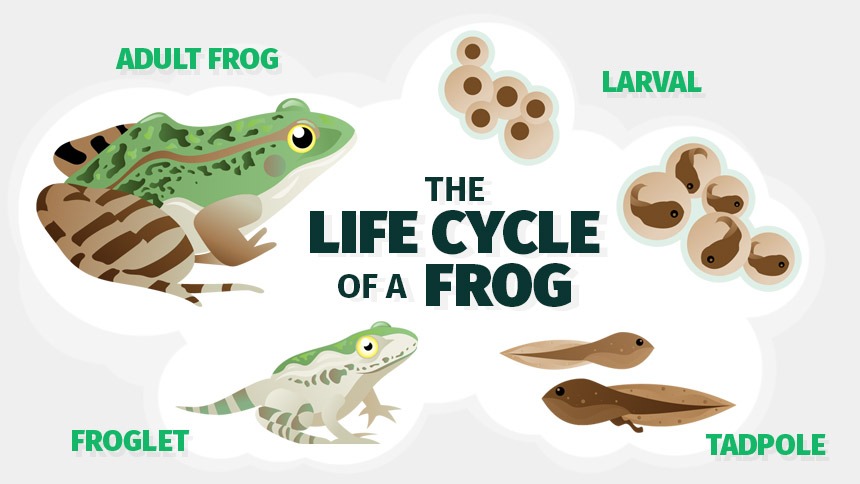

But despite these differences, most frogs share a common lifecycle. They are born as eggs, develop as tadpoles, begin maturing as froglets, and live the majority of their lives in their final form: an adult frog. This metamorphosis provides a point of connection across all varieties and breeds of frogs.

Both frogs who develop along this common life cycle and frogs that veer slightly away from it are fascinating creatures that have the metamorphic process down to a science.

Page Contents

Metamorphosis in Amphibians

This term is derived from a Greek word meaning “transformation,” and remains an apt descriptor. As its etymology suggest, metamorphosis refers to when an animal undergoes a transformation at the beginning of or throughout its life.

Metamorphosis is a biological process wherein an animal physical changes and develops after hatching or birth. It usually involves a drastic change in appearance and body structure, which may result in new or lost appendages, features, and/ or organs. Insects, fish, crustaceans, and amphibians (just to name a few) all undergo metamorphosis.

Holometaboly is when an animal undergoes complete metamorphosis, while hemimetaboly refers to when an animal only undergoes partial metamorphosis.

Frogs and toads are two of the most prominent types of amphibians that undergo metamorphosis. With some exceptions, they generally develop from a larval or egg stage to a fully formed adult, passing through stages as a tadpole and froglet in between. The most significant changes are to their lungs, which become gills, and body structure, which changes from a tail to arms and legs. Their mouths, eyes, heads, internal organs, and neural networks all also undergo changes, though to a lesser visual degree.

The Stages in the Life Cycle of a Frog

There are a few stages frogs go through during their life cycle. Listed below are the stages with a detailed explanation of each part of their life.

The Larval/ Egg Stage

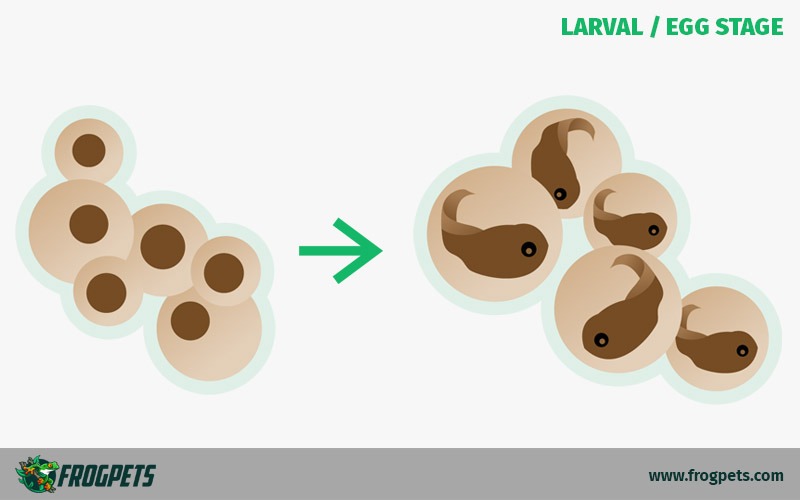

Female frogs lay large clusters of eggs that float on water in a sort of jelly-like mass. Once fertilized and laid, the eggs will absorb water and swell rapidly. To increase chances of survival, females may lay dozens or even hundreds of eggs.

Eggs are usually laid in calm or static waters, since all frog eggs since moisture to survive. The chosen location usually has two main benefits: the presence of predators is minimal and the calm waters reduce the changes of prematurely rupturing and killing the eggs. Any eggs above the waterline are in danger of being eaten, succumbing to lingering frost, being damaged by falling debris, etc.

Healthy eggs will be translucent, and onlookers will be able to see the embryo inside. Unhealthy or dead eggs will turn white or opaque.

The embryo initially starts as one central piece, but soon begins to split and multiply. As the embryo continues to multiply, it will begin to resemble a raspberry. At this point, the embryo will begin developing into a tadpole. The tadpole will move around in the egg and become increasingly active as it prepares to hatch.

Egg and Nesting Adaptations

Some frogs have developed specialized fertilization and nesting adaptations to increase their offspring’s chances of survival. Though not common among all types of frogs, there are a good number of species that diverge from the mating, fertilization, and clutch-laying behaviors described above.

The cost foam-nest tree frog is one such example. On tree branches overhanging still and stagnant water, this frog lays her egg masses in a giant, cocoon-like structure made of whipped sperm-turned-foam.

The foam will harden as a result of its subtropical and tropical dry forest habitats, protecting the moisture inside and preventing the eggs from drying up. When it finally rains, the foam will return to its original state, drip down and deposit the tadpoles into the water below.

Vizcacheras’ White-lipped frogs also prefer to mate and nest outside of water. On land, males construct subterranean volcano-shaped chambers or nests made of mud and other materials, where females will enter and the couple will engage in spawning. The eggs are deposited in and kept moist by a secondary nest or layer of foam.

Rains and floods later dissolve the outer nest and carry the eggs to water, where the tadpoles hatch and continue their development.

Other frogs skip the egg stage entirely and give birth to fully-formed tadpoles or live froglets, such as varieties of the Asian fanged frog, members of the African genus Nectophrynoides, and the possibly-extinct Puerto Rican golden frog.

The Tadpole Stage

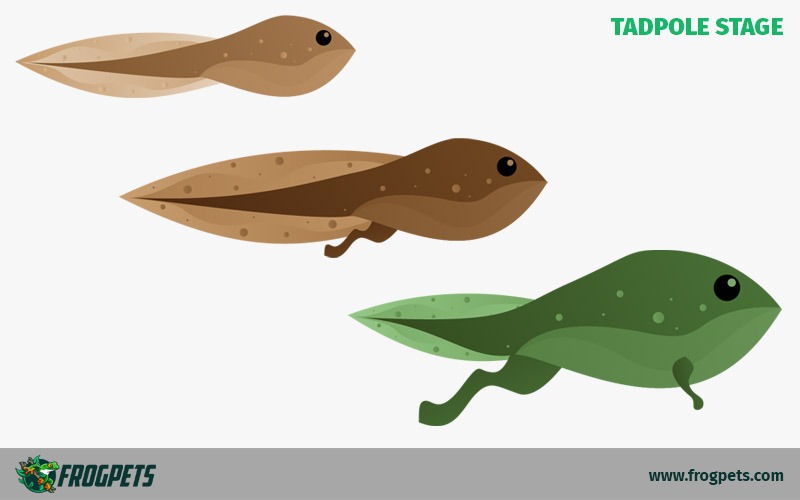

Though tadpoles hatch from the eggs with gills that allow them to breathe underwater, where they will spend the majority of this stage, the gills are poorly developed. As a result, tadpoles are poor swimmers during their first days of life.

Using sticky organs between their mouths and “bellies,” tadpoles will attach themselves to floating weeds, grasses, and other anchors in the water. They will survive by eating/ digesting the remaining yolk from their eggs, which is stored in their stomach after hatching for this purpose.

After approximately a week, their gills and long tail will strengthen and the tadpoles will begin to swim. At this point, they survive by eating plant matter and algae available in the surrounding water.

This stage lasts for several weeks, during which period the tadpoles will begin to develop the following features:

- Lungs

- Teeth

- Hind Legs

- Head

Over the course of a few weeks, skin will slowly begin to grow over the gills as the lungs develop. The lungs will not be fully functioning until the end of this process at the froglet stage, necessitating the continued presence of gills. However, the tadpoles may begin to breathe air above the waterline for limited periods of time.

Tiny teeth will begin to form, helping them better eat and digest the plant matter and algae. They may add proper plants and dead insects to their diet. These teeth will also allow them to oxygenate the food and better feed their developing guts, which will be long and coiled to help them receive the most nutrients possible from their diet.

Related

Their hind legs will also begin to develop during this period, and they may experiment with kicking motions underneath the water. However, they will still have a very limited range of motion, as their front legs have not developed yet. Bulges may appear where their front legs will eventually form, but this step is reserved for the froglet stage.

Though less developed, the tadpole’s head will also begin to take form. It will transition from a circular shape to the more distinct oval shape of adult frogs.

Socialization is another distinct feature of this stage. By the end of their time as tadpoles, these juveniles will be very social! They may already be showing signs of schooling and other mature behaviors.

The Froglet Stage

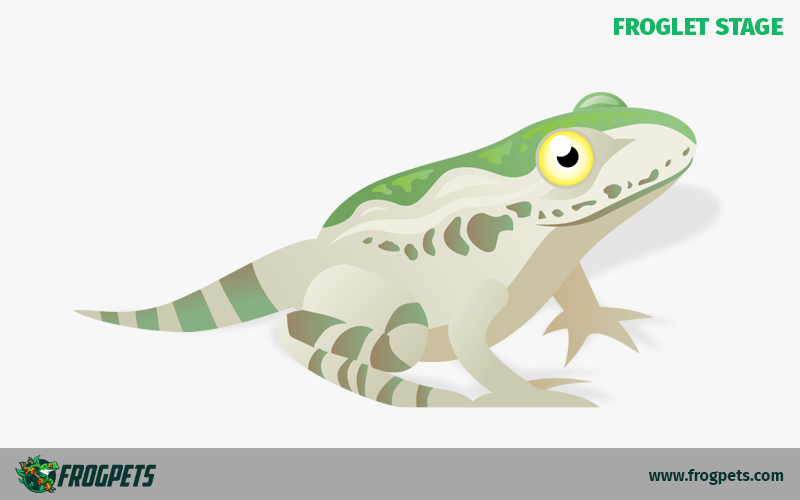

As the tadpole grows, it will transition into a froglet. During this stage, the juvenile frog will finally develop its front legs, its tail will grow shorter and eventually disappear, and its gills will fade in favor of fully functioning and strong lungs. Essentially, it will look like a mature frog with an increasingly shorter tail.

A tadpole’s tail actually stores nutrients, and the froglet will begin taking advantage of this food source during this stage. Until its tail is gone completely, a froglet technically doesn’t need to eat, though it may still munch on plants, plant matter, algae, and insects.

The tiny teeth will develop into cane teeth along the froglet’s upper jaw, called maxillary teeth. They may also develop teeth on the roof of their mouth, called vomerine teeth. However, these teeth are not what chew up their food. Instead, they’re mainly used to hold prey in place until the froglet can blink their eyes and push the food down their throat.

When its front legs and lungs are finally ready, the froglet will emerge from the water and begin its life on dry land. It will still be small and may take some time to grow to the standard size and weight for its species.

The Adult Frog Stage

As an adult, frogs live the majority of their life on land. They eat insects and other land-dwelling inhabitants. Frogs take an average of two to four years to become fully mature adults, but they have completed their growth cycle by sixteen weeks (at the longest). Some frogs are less than an inch long, while others can grow close to 12-inches.

Habitat, diet, lifespan, and behavior will all depend on the species of that particular frog. However, as a general rule most frogs tend to stay near accessible water, are omnivores, live at least one year, and are social creatures.

It is during their adult stage that they will begin mating and reproducing and the frog life cycle will begin again.

Courting and Mating Behavior

Though some frogs do deviate from “normal” behavior, frogs generally all court and mate the same way. The males gravitate toward fertile females or females choose virile males, they engage in amplexus and external fertilization, and a clutch of eggs is deposited in the water to hatch and grow.

Males tend to gravitate towards females that are large and have similar or bright color markings. Females are usually pickier than males.

They tend to prefer males that are loud, which they use as an indication of virility and strength. For example, the wrinkled toadlet (which is actually a frog) has been known to take up to four nights to analyze the calls of various males and finally select a mate. This is why frogs croak after it rains.

The description given above is fairly simple, but some mating behaviors can actually be quite complex and varied. Physical characteristics, vocal sounds, and the setting can all have an impact on how males and females interact. Behavior may be further impacted by mating and fertilization adaptations that have developed over time.

Amplexus

Though not all mating behavior is the same, frogs generally engage in amplexus when mating. Amplexus refers to the common position male frogs take, wherein they climb onto the female’s back and clasp underneath her head or “waist,” either just behind her front legs or in front of her hind legs.

Amplexus may last for brief periods of time or span the length of several days. During this time, the male frog will fertilize the eggs as the female lays them. Male frogs develop pads on their forelegs to help them during this period, better securing their position on the female and ensuring maximum fertilization potential.

Types of Amplexus

There are actually seven different types of amplexus, the most common of which is described above. But even this type can be broken down into two additional forms of amplexus.

Inguinal amplexus is when the male clasps the female around her “waist” near her hind legs, while axillary amplexus is when a male clasps the female just behind her forelimbs.

“Glued” amplexus is when males stick themselves to females using mucus skin secretions. These secretions ensure the males will stay on the females long enough to fertilize the eggs and solve physical problems present in species such as the common rain frog.

This type of frog has an especially rotund body and short arms, which prevents males from being able to engage in more traditional amplexus positions.

Another type of amplexus involves the male releasing his sperm onto the female’s back, where it runs upward and fertilizes the eggs as they leave the female’s ovipositor.

Vocal Sounds

Croaking and mating calls are another common behavior, and even “earless” frogs have been proven to be able to engage in it (and with surprising accuracy, too). Frogs croak by using their vocal sac, is a flap of skin at the front of their throats near their vocal chords.

When inflated, the sac fills with air and expands. Frogs can also move air from their sac back and forth over their vocal chords. These actions produce croaks, chirps, trills, ribbits, clicks, rasps, and other sounds.

Male frogs croak to attract mates (i.e., impress females) and warn off competitors. Female frogs may also produce sounds to attract males and otherwise communicate during the mating process.

Mating Settings

Mating may occur in the water or on land. Frogs were conventionally believed to only mate in water since eggs require moisture to survive and grow to maturity, but an increasing number of species have been found to mate and lay eggs terrestrially. These eggs may be laid on the ground, in trees, or on plants. However, all eggs are eventually transferred to water to hatch and develop.

Generally, frogs prefer to mate at night. This reduces their exposure to predators and other threats and increases the likelihood of a peaceful mating. Frogs may even use the lunar cycle to coordinate their gatherings, which can result in various species all coming together to mate at the same time.

Mating and Egg Fertilization Adaptations

Similar to how some frogs have developed specialized nesting adaptations, many frogs have also evolved to show mating and egg fertilization adaptations.

Once again, the coast foam-nest tree frog is another prime example of this. The frogs engage in what is commonly described as the most extreme show of frog (and even vertebrate) polyandry, a mating pattern in which multiple males mate with one female.

During mating and fertilization, the female releases her eggs and up to a dozen males gather around her to all fertilize the eggs. They then whip the produced sperm into a foam nest with their front legs. As a result, these eggs have a significantly higher survival rate than eggs produced by “monogamous” matings.

Another type of tree frog, the Coqui, also has a mating behavior different from that of most frogs. Though male frogs will climb onto a female’s back, they do not engage in amplexus. Instead, they will remain inactive, and after a period of time determined by the female, the female will either dislodge the male or lock her legs around his back legs. At this point, they engage in internal fertilization as opposed to external fertilization.

The European common frog engages in clutch piracy, wherein males steal eggs freshly laid by females and take them away to a secluded area to fertilize them. This is caused by the disproportionate ratio of males to females. Since there are not enough females for mating, males have shifted their focus to the eggs themselves.

Males will wait until the eggs are left unguarded, steal clutches while the original parents are still mating, and search for already-stolen clutches to re-fertilize. All of this results in clutches that have two or more fathers. But this thievery has a bright side: it has led to a whopping 90% fertilization rate for eggs, resulting in a thriving population.

Accidental Matings and Breeding Bloopers

Many frogs are sexually dimorphic, which means that there are distinct differences between males and females. These differences may show in their coloring, physical characteristics, vocals, or take another form. But there are some species in which males and females are remarkably similar, leading to courtship blunders.

During the mating process, some frogs male frogs may mistakenly trap another male in amplexus, at which point the trapped male will protest via release calls.

Even when male frogs find females, they may not engage in amplexus with the correct species. Males often gravitate towards females that are larger and display bright colorings, and don’t always discern between their own species and a different one. Similar mating calls or vocalizations can further confuse matters.

Besides mating with other males or the wrong type of females, some male frogs also try to mate with inanimate objects. They may remain in amplexus for hours before realizing their mistake and searching for a more viable companion.

Parental Behavior

Though many species absolve themselves of parental duties after the eggs are laid, some frogs are comparatively maternal or paternal. Rather than allowing the eggs to incubate underwater, they may carry the egg sin their vocal sacs or abdomens.

Strawberry poison dart frogs are a prime example of this. Both parents help to protect and rear the eggs until hatching. After being laid on land, the fertilized eggs are kept moist by the father, who urinates on them regularly.

Once hatched, the mother then carries each tadpole on her back to a plant such as the bromeliad, which has a pool of water between its stem and leaves. She deposits each tadpole in a pool of water and returns periodically to lay unfertilized eggs, which the tadpoles will feast on as they mature.

Related:

Surinam toads (which are actually a type of aquatic frog) also have a unique parenting method. After fertilization, the male pushes the eggs onto the female’s back.

The eggs will stick to her skin, which will grow up and around the eggs to form an enclosed protective structure. Safe under her skin, the eggs will hatch and complete their lifecycle. When they reach maturity, the toadlets will push free of their mother’s skin and swim to the surface.

And the gastric brooding frog, now tragically extinct, is another example. These frogs swallowed their eggs and allowed them to develop in their stomachs. During this period, they refrained from eating or digesting food until the eggs were ready to hatch. At this point, they climbed out of their parents’ mouths and matured in the water.

The Frog Life Cycle Over Time

Frogs are fascinating and complex creatures that display a variety of behaviors. During mating season, they are no less diverse. Though most frogs engage in amplexus and external fertilization, there are many forms of amplexus and fertilization techniques. But despite this wide array of possibilities, frogs are generally united by their life cycle.

Beginning as clutches of eggs, embryos develop into tadpoles and froglets, before emerging as adult frogs ready to mate and begin the life cycle anew.

This simple metamorphic process has withstood the test of time, adapting to harsh conditions and adverse environments to emerge victorious. Today, frogs are one of the most diverse and widespread species, some of whom still remain undiscovered and hold untold future scientific delights.

Leave a Reply